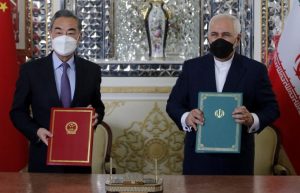

China’s substantial investment in development finance across Southeast Asia has positioned it as a major player in the region. However, new research from the Lowy Institute reveals that China faces competition from other regional partners, including Japan and South Korea. While China’s funding focus is primarily on the energy sector, there is room for Western donors to strengthen their presence in Southeast Asia.

This article explores the potential for Western partners to enhance their development initiatives, communicate their efforts effectively, and adapt their strategies to compete with China.

China’s Development Finance Landscape:

China allocates approximately $5 billion annually to development finance in Southeast Asia, with a significant portion dedicated to large infrastructure projects in Indonesia, Laos, and Cambodia. While China leads in the energy sector, Japan surpasses China in financing the transport sector, often on more favorable terms, and South Korea matches China in telecommunications investments.

Gap between Promises and Delivery:

China has made ambitious promises to Southeast Asia but struggles to fulfill them entirely. Despite signing projects worth $12 billion annually between 2015 and 2021, the actual volume of official development finance provided falls short. Delays in large infrastructure projects, compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic, have hindered progress.

Western Donors’ Role:

Western partners, including the United States and Australia, contribute a diverse range of development aid to Southeast Asia. While China provides around 20% of overall development aid, Western donors, such as the U.S., stand out for their generosity, offering grants without repayment expectations.

Western governments need to better communicate their support and align projects with Southeast Asian countries’ national development objectives.

Responding to Crisis and Flexibility:

Western donors have proven responsive during crises, unlike China. Australia tripled its development spending during the COVID-19 pandemic and reoriented programs toward pandemic response.

The U.S. holds a significant share of health-related assistance in the region. Flexibility and adaptability in times of crisis are essential for Western partners.

Communication and Strategic Advantage:

Improved communication is crucial for Western countries to effectively compete in Southeast Asia. Framing support as a means to enhance productivity, regional competitiveness, and catalyze private sector investment is essential.

Concrete examples of successful private sector involvement should be highlighted to demonstrate the impact of assistance.

Adapting to Leverage Development Lending:

Western partners can leverage their strategic advantage by embracing development lending. Grant assistance alone may not have the scale required to make a significant impact in rapidly growing economies like Indonesia and Vietnam.

Alternative financing mechanisms, such as loans, guarantees, and equity investments, can be employed to expand development initiatives and address pressing needs like climate change.

Conclusion:

China’s dominance in development finance in Southeast Asia presents both challenges and opportunities for Western partners.

By improving communication, adapting strategies, and exploring innovative approaches such as development lending, Western donors can compete effectively, leverage their strengths, and contribute to the region’s sustainable development goals.

Embracing a distinct and forward-thinking approach will be crucial to navigate Southeast Asia’s evolving economic landscape.